Ultra-low Energy Loss in Biomolecular Motor

Figure out the underlying mechanism of ~100% efficiency for bacterial flagellar motor.

Overview

Biological systems are replete with fascinating motor machines that can be categorized as either linear or rotary motors. Linear motors like kinesin, dynein, and myosin utilize ATP hydrolysis to generate energy for locomotion. In contrast, rotary motors such as the bacterial flagellar motor (BFM) and ATPase derive energy from the electrochemical potential difference of cations across the cell membrane. This project focuses on the bacterial flagellar motor.

The bacterial flagellar motor (BFM) was first implicated in the seventeenth century when Leeuwenhoek observed swimming bacteria. However, the intricacies of bacterial mobility, including the flagellar filament and motor spins, remained unnoticed for 300 years due to the limitations of optical microscopes. It was only in the mid-20th century that the flagellar motor’s movements gained renewed attention.

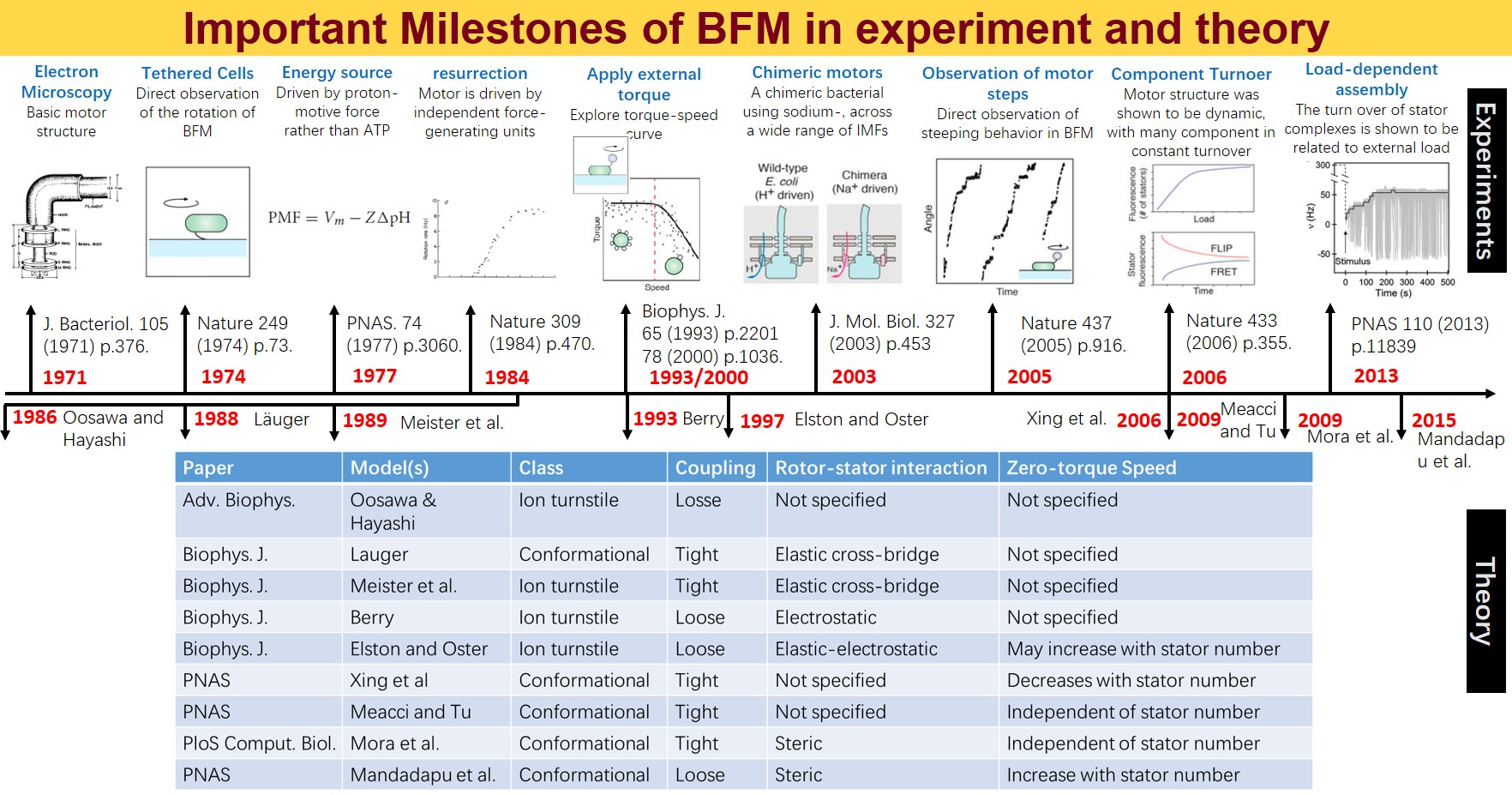

Key Milestones and Research Background

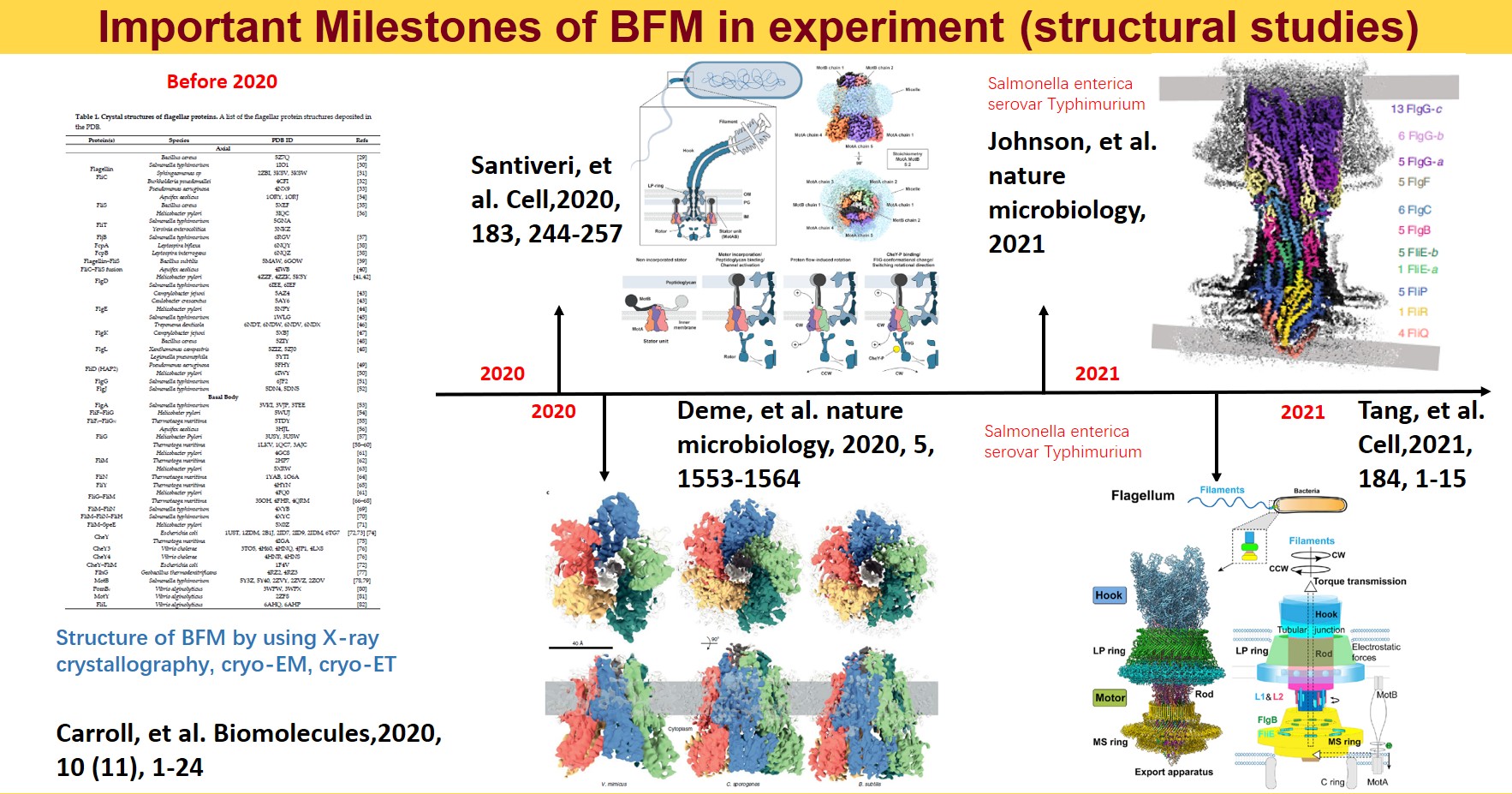

Although the BFM has been a subject of study for decades, detailed modeling was hindered by a lack of atomic-level structural data until recent breakthroughs. Before 2020, most structural analyses were summarized in a review by Liu Jun’s group at Yale. Significant advancements occurred in 2020 when two papers published atomic-level structural data of BFM. These findings were crucial for understanding how BFM converts chemical gradient energy into mechanical energy. However, our research does not focus on these aspects.

In May 2021, the atomic accuracy analysis of the flagellar basal body by cryo-EM was published almost simultaneously by teams from Zhejiang University and Oxford. This discovery is the primary motivation for our project, revealing potential key mechanisms within the structure.

Innovative Findings and Current Research

The basal body of the BFM functions as a rotary motor composed of several rings (C, MS, and LP) and a rod. Remarkably, the LP ring acts as a bushing, supporting the rod’s rapid and stable rotation with minimal friction. Notably, the maximum rotation speed has been recorded at 1700 revolutions per second, surpassing even that of an Aero Engine. Despite its asymmetry and the high-speed rotation, the system maintains stability and converts electrochemical potentials to mechanical work with near-perfect efficiency.

This phenomenon can be viewed through the lens of liquid-solid and solid-solid interfaces:

- The gap between the outer surface of the rod and the inner surface of the L ring, approximately 6 - 7 Angstroms, accommodates one or two layers of water molecules, creating a liquid-solid interface.

- Conversely, the gap between the rod and the P ring is narrower, about 2-3 Angstroms, forming a solid-solid interface without water.

Future Directions and Challenges

Our project aims to uncover the underlying mechanisms of these observations, which could inform the design of new super-lubricant interfaces and enhance our understanding of microbial-environment interactions. Currently, we are exploring two approaches:

-

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: We are conducting all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of the entire system, which comprises about 2 million atoms. However, due to hardware limitations, achieving the necessary microsecond timescale is challenging; our simulations currently reach only nanoseconds. We are considering leveraging machine learning to accelerate these simulations.

-

Thermodynamic Modeling: Considering the energy scale of biological motors is comparable to thermal fluctuations in the environment, we hypothesize that the motor might utilize thermal energy to overcome friction. A simplified and abstract thermodynamic model could validate this innovative concept efficiently.